By Mike Fotopoulos (@irishoutsider)

The winter of our discontent is over. MLS Season 20 is here and the new CBA is in the books. While we will likely have to wait for most of the details and watch new rules inevitably “reveal” themselves, there is a lot to learn here. The process has given us another look into the league’s overall goals, and more importantly, the owners’ priorities.

The results have been largely disappointing. If you are an idealist, this is a compromise delivering more of the same, and maybe just a little bit more on top. The cap will increase 7% a year for five years, topping out at about $4.2M in 2019. DP slots remain unchanged, though the cap hit will likely increase to remain a fixed % of the overall cap. Finally, free agency arrives for players 28 and up, with at least eight seasons of MLS service time. Those of us looking for a utopian MLS “letting the bull run,” will need to keep dreaming.

The owners’ position here and their motivations all seem to point in the same direction, maximizing the value of the franchises. This is accomplished primarily by increasing sponsorship and broadcast revenues while keeping labor costs down. These streams are crowding out gameday revenues as the league’s primary source of income. Both also have the potential to grow further and faster than traditional staples like tickets sales and merchandising. As a “brand,” the league has an attractive business model here, with more likely suitors lining up for a piece of the action. These new potential markets aren’t viable without the ROI possibilities of a growing media property.

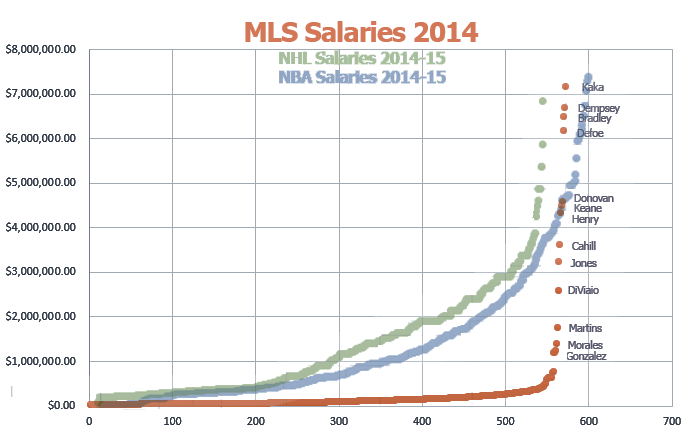

For the average American sports fan, the value of the league is primarily governed by its star power, not the rank and file. Take a look at any MLS advertising and they are taking pages right out of the NBA / NHL playbook. Dempsey! Bradley! MLS ON ESPN! Talented unknowns on global average salaries aren’t going to move the Nielsen meter. To draw a completely unfair comparison, the vast majority of the football viewing world watches Barcelona for Messi and friends and not for the triumph of skillful team counterpressing. Relating this back to MLS, the league needs to save as much of the coming windfalls for “talent.”

Dempsey (and very likely Beckham) set the precedent here, showing that the owners as a group will pool their resources to bring in a star player. While he can only play for Seattle, he can increase their local gates once or twice a season and pay dividends on future league sponsor / rights deals. Gerrard, Villa, and Kaka, etc follow this trend to varying degrees of league involvement, though the overall goal is the same: create top-line value by signing as few big contracts as needed, the minimum viable dose. Top-heavy rosters may not be optimal in a football sense, but they act as leverage for franchise value.

Under this system, it becomes much clearer why free agency would be a non-starter, especially for owners like RSL’s Dell Loy Hansen. While RSL is a model small-market club, Mr. Hansen’s investment is controlled by the league’s ability to generate a national audience and his ability to field a team with strictly defined costs. Without accusing development efforts as lip service, part of that cost structure is producing homegrown talent at low cost, and retaining that talent efficiently. This also requires keeping existing core players together as long as possible. If Mr. Hansen can also control a youngster’s rights long enough to profit from a foreign transfer, that’s excellent business. Where the CBA has settled on this protects these issues for RSL and clubs with similar views.

Those that have directly lost the most from this perspective are the once and future journeymen of MLS. The system has them in purgatory for at least the near-term, unable to massively outperform current contracts, and highly unlikely to see stronger offers from outside of the league. This is the core position taken during the negotiations, and it has to be cut and dry from the owners’ perspective. They don’t have the resources (yet) to consistently improve rosters in the 150-350k range. That money is better spent on the latest shirt-selling import. More optimistically, once a player reaches 28/8 the DP thresholds are now high enough that teams could double up a salary without locking down a slot. Overall, the deal stretches out their clocks more than they would like without serious breakout seasons.

The future is positively blinding for the league if they can maintain the current tack. The potential is there to earn legitimate multiples on their salary costs, and we likely won’t see an equitable split for the players until the stakes get much higher. Owners want to position the league to earn eye-watering broadcast rights, but the current situation will be harder to maintain if they succeed. The main deal with ESPN/FOX resets after eight seasons, so it may actually benefit the owners to have a five-year agreement with the union. While there is a likely future where MLS’ ratings and revenue continue to grow, it would be optimistic to expect this to occur between the TV deals. With that in mind, this may be the last CBA discussed in strict dollar terms versus percents of league wide revenue.

Major League Soccer has promoted itself as a “League of Choice” for the best players in the world and certainly the best America has to offer. The new CBA lines up with that vision. Even if many of us would like for the league to spread the wealth around a bit more, the strategy is sound. By focusing on the very top of the rosters and locking down on the rest, the league creates value where it wants it most: broadcast rights and franchise value.