NEW YORK CITY FOOTBALL CLUB: POSTSEASON PREVIEW

/Slow, then fast. That’s how NYCFC plays soccer.

A lot of pixels have been spilled, especially by my colleagues over at The Outfield, trying to describe the tactics that have elevated NYCFC from the unpredictable side that stumbled through a string of draws to start the year into the even less predictable side that’s shapeshifted its way to the most successful season in the club’s short history.

There’s an adherence to style over system, certainly. There’s a dash of Pep ball and some rudimentary juego de posición. This is a team that can beat you with a front two or a front three, with a back three and a back four, and above all with Maxi Moralez. As Joseph Lowery put it for The Athletic, Dome Torrent’s side strikes a “balance between fluidity and rigidity, allowing his players to move, but under specific guidelines that encourage structure.”

But that all sounds sort of abstruse. You’d probably rather watch a pretty goal, right?

On loop 🔁 pic.twitter.com/yBw1DhriZT

— New York City FC (@NYCFC) July 27, 2019

The play starts in a deep possession pattern—too deep, really—as Sporting Kansas City’s forwards jump a backpass to the keeper and NYCFC’s center backs respond by splitting wide to the touchline: a statement of intent to dare the press forward and play out of the back at all costs. Sean Johnson buys his team room to breathe with an audacious short-range chip over the first line of pressure, and what looks like an insignificant square pass from Alex Ring to his defensive midfield partner Keaton Parks breaks open the play as Parks finds Moralez idling in the center circle with his foot on the gas.

A charging run. A quick switch of play to a wingback. A dummy, a one-touch throughball, and the coup de grâce from the optimal assist zone to a full menu of runners: near post, trailing man, and far post, where Anton Tinnerholm does the honors.

It takes twelve seconds from the time Maxi turns at midfield to that fluid finish. His teammates aren’t “in position”—that’s a defensive midfielder laying in the endline cross to an outside back—but somehow everyone’s exactly where they need to be. The opponent never recovers its shape.

Slow, then fast.

“That,” Dome said of the goal, “is the New York City Football Club style now.”

2019 SEASON REVIEW

Appropriately, things started slow. The lineups from that sluggish 0-5-1 stretch from March to mid-April look a little dubious in hindsight, featuring a cast of names (Jonathan Lewis, Jesús Medina, Ben Sweat, Ebenezer Ofori) who would soon play themselves out of Dome’s lineup. But the coach’s willingness to give young players a shot paid off big with James Sands and Valentín Castellanos, who grabbed lineup spots and never looked back, and eventually Keaton Parks, who fought his way from cause célèbre in the spring to starter by summer.

The problem was at striker—more specifically, the absence of one. After taking its time scouting replacements for David Villa, the club lost out on a couple late bids and opened the season with no clear plan at center forward. Dome toyed in the preseason with converting Castellanos from wing to striker, but on opening day he lost his nerve and instead moved Moralez—all 5'2" of him—out of midfield and between the opposing center backs. The knock-on effects were ugly. Not only did NYCFC lose its engine in possession, as Moralez dropped from 70 passes a game in 2018 to 49 in the first six games of 2019. Not only that, but his creative midfield role fell to Ring, who for all his gifts is not exactly a creative midfielder. I mean, just look at the early-season sonar below: Ring's passing in the attacking half was erratic, which meant NYCFC's ball progression was erratic, which meant Dome had to spend every postgame presser not so subtly reminding fans—and maybe his bosses—that he'd been promised a striker.

A snapshot of Ring’s pass sonar from early April 2019, when he was playing as NYCFC’s most advanced midfielder. Length represents pass count by angle, color is average distance (yellow is longer).

Fortunately, the cavalry was on the way. It came in the not particularly scary-looking form of human hang-loose emoji Héber, a journeyman Brazilian striker who would finish the season with an extremely scary—like, better than Zlatan and Josef scary—nonpenalty goal plus assist rate. Just as important as Héber's work in the box was the well rounded game he'd developed in Croatia, as he spearheaded NYCFC's press and dropped into his old left wing stomping grounds to help Moralez, who’d happily returned to midfield, link the buildup to the attack.

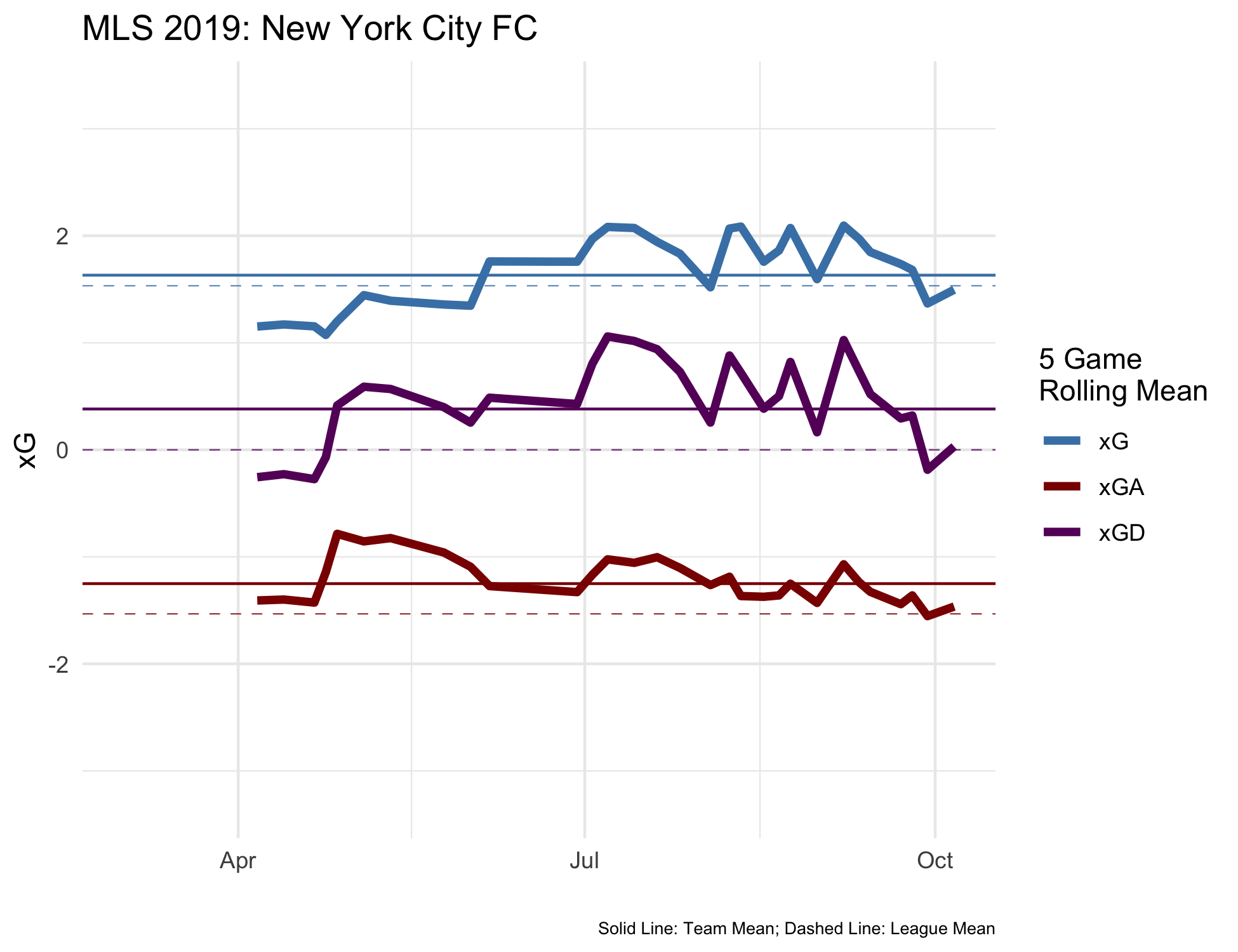

Around the same time that Héber rearranged NYCFC’s front end, an equally important shift was happening at the back. Sands, who’d started the year as a defensive midfielder who sometimes dropped between the center backs, became a center back who sometimes moved up to join the midfield. What sounds like semantics turned out to be a sea change for NYCFC’s defense, which shot from 15th in the league for home-adjusted expected goals allowed (1.25) through the first six games, playing a four-back formation, to 2nd place (0.77) over the next six in their new three-at-the-back shape. See, in the graphic above, how the red rolling xGA line hits a dramatic cliff in April? That’s how sharply this unit improves when you push Tinnerholm and Rónald Matarrita from fullback to wingback, let Maxime Chanot and Alexander Callens patrol the wide spaces, and count on the homegrown teenager Jimmy Sands to hold the whole thing down in the middle.

Looking back, the turning point of the season was the April 13 visit to open Minnesota’s new stadium. NYCFC started the game in a 3-4-3 with Moralez and Ismael Tajouri-Shradi pinching in from the wings to overload the midfield behind Taty Castellanos at striker, then switched in the second half to a 4-2-3-1—and, startlingly, they looked pretty good in both shapes. The white-hot May road trip in NYCFC’s shiny new 3-4-3 was too good to last; injuries and wacky MLS scheduling eventually forced Dome to adopt different formations when it became apparent that Ring wasn’t a comfortable substitute for Sands at center back. But by that time something had clicked. The players just got it. Whatever shape the team started the game in, they usually cycled through two or three by the end of it, reacting on the fly to opponents’ tactics faster than the other coach could adjust. Instead of looking confused by Dome’s tinkering, his team was invigorated by it, and the players’ rapidly improving positional sense helped them cover for each other during a rotation-heavy back half of the schedule.

NYCFC finished the regular season with 64 points and a +21 goal differential, both better than they’d ever managed under Patrick Vieira, and wrapped up the East’s top seed with a week to spare. This team can play soccer. But what can data tell us about how they do it?

In Possession

Goals: 1.85 per game (2nd in MLS)

Expected Goals: 1.44 per game (8th in MLS)

Possession [pass ratio]: 57.4% (2nd in MLS)

Final Third Passes: 101.9 per game (18th in MLS)

Press Resistance [xPass in first two thirds]: +0.55% (15th in MLS)

Let’s start with what we know: they play slow, then fast. Maybe it’ll help to see that in viz form.

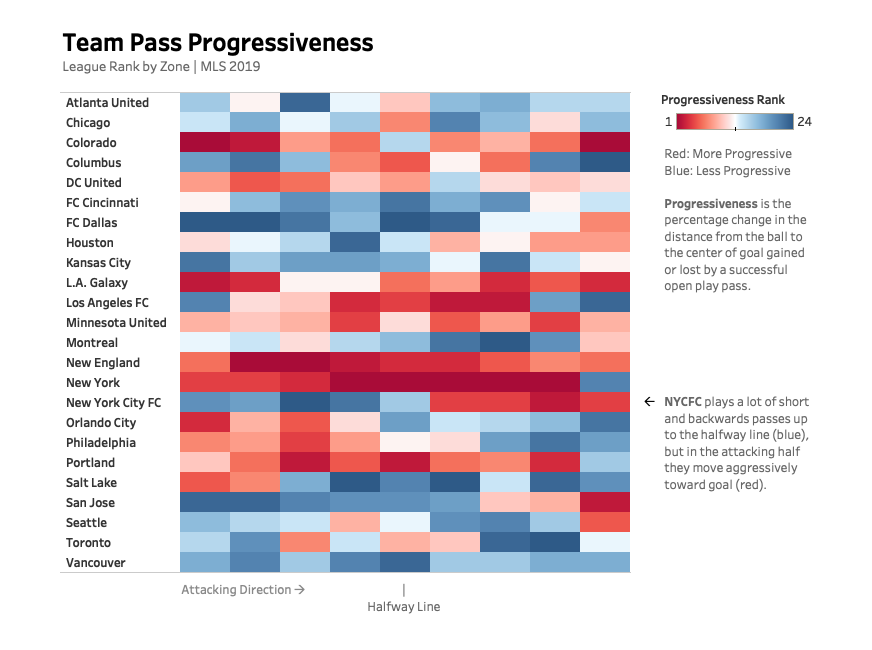

Most teams fall into one of three camps on the ball: your cautious possession teams, your direct high-tempo teams, and the styleless blobs that are just happy to be there. Not this NYCFC. They are a team of two halves. From the goalkeeper to the center circle they are a pineapple fallen straight from the Guardiola coaching tree, all gradual passing patterns and positional play. Cross the halfway line, though, and they become one of the most direct teams in the league, a rapid strike force of forwards and wingbacks hurtling straight at goal. Nobody else in MLS plays quite like it.

It’s also not at all how Dome’s team played last year. When he took over from Vieira halfway through 2018, Torrent’s first order of business was fixing a possession game that was losing the ball too often in dangerous positions. He did it by emptying out the midfield and playing vertically through the wingers in a wide 4-2-3-1, successfully shifting the action into the opponent’s half. It seemed like common sense: the more time the ball spends away from your goal and closer to theirs, the more likely you are to win. But the roughing up NYCFC took from Atlanta United in the playoffs (there were, by my rough calculations, eleventy billion fouls between the two teams in the leg at Yankee Stadium) revealed a team that was too quick to bail out of the buildup and look for a long ball over the top. They weren’t in control. As Dome likes to say when his players decline to pass their way through the opposition, they weren’t “brave” enough.

So NYCFC spent the offseason retooling the buildup. First, they signed players for their comfort on the ball (Tony Rocha, Keaton Parks, Alexandru Mitriţǎ, even SuperDraft backup keeper Luis Barraza). Then they went to Abu Dhabi and trained so much on building out of the back that by the last game of the preseason, a snoozer where NYCFC struggled to break down lower-division Nashville, you started to wonder if they had forgotten the game has other phases that might be sort of important too. NYCFC had worked hard to recover its discipline in its own half, but in the process, the team had reverted to something that looked kind of like Vieira’s back-left-side possession vortex—the same problem Dome had fixed the summer before.

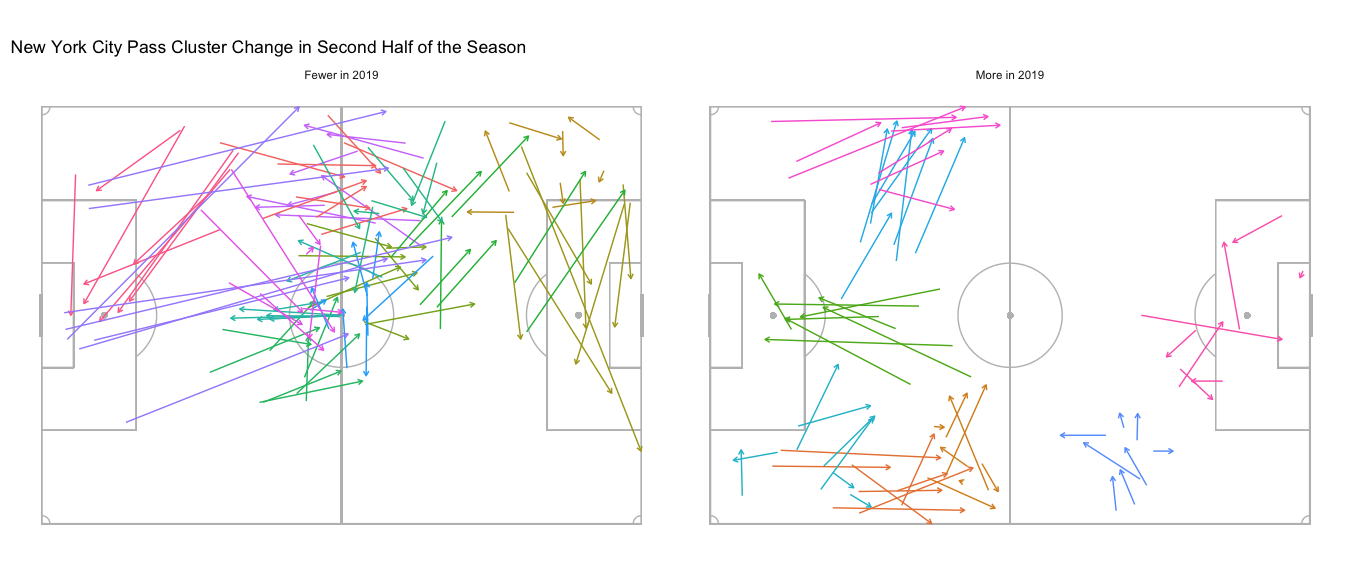

By the end of the regular season, the data still showed a team that by some measures appeared stuck behind the halfway line. Using Cheuk Hei Ho and Eliot McKinley’s method, we can compare NYCFC’s most and least common passes in the second half of 2019 with the same from the second half of 2018. Even after we apply an even game state filter to account for the fact that the 2019 team was leading more often (and thus less likely to face bunkered defenses), nearly all of the pass types the team does more of this season are in the buildup, mostly involving the wingbacks. In the image on the left, we see what they are doing less of: short passing around the center circle and attacking from the left wing. If you didn’t know better you’d probably guess this was a team that had gotten worse, not better, at attacking.

Per expected goals, actually, that’s true. From the time Dome took over last June to the end of the 2018 season, NYCFC averaged 1.68 home-adjusted xG per game, good for fourth in the league. Over the same time period in 2019, they are at 1.54 and seventh. As best our model can tell, this team is creating fewer or worse chances than last season and probably getting a little fortunate on their conversion rate.

That makes sense, honestly. Dropping a player from the attack to the back line, as NYCFC does when it goes three-at-the-back, ought to cost you something in shot creation. As for the corresponding decline in attacking-third passing, that probably owes something to NYCFC swapping wide wingers who cautiously circulate the ball for Alexandru Mitriţǎ, a low-touch, high-progressiveness guy who came here to chew bubble gum, score dribbling highlight goals, and never be in possession of any bubble gum. Castellanos and Héber are around the striker median for involvement, so you’re not getting a ton of possession play from your strikers, either. Sometimes Maxi’s a one-man show.

The good news is that stuff seemed to be changing toward the end of the season. With Sands out, Dome played more four-back shapes, freeing up a midfield slot. Mitri started to notice that he had teammates, raising his expected goal chain by 25% in the last two months of the season. You can see from the team’s blue rolling xGF line in the plot up top that their chance production did get better in the summer. Even so, the numbers suggest NYCFC’s a good attacking team that only looks like a really great attacking team thanks to a generous G-xG.

Out of Possession

Goals Against: 1.15 (3rd in MLS)

Expected Goals Against: 1.11 (2nd in MLS)

Final Third Passes Against: 91.7 per game (3rd in MLS)

High Pressing [xPass against in first two thirds]: -1.41% (2nd in MLS)

You can make a better case that NYCFC’s new Crouching Tiger, Hidden Héber fighting style is helping on defense. The team’s expected goals against are down by 7.5% this season, perhaps thanks to playing more 3-4-3 and less Ben Sweat. That’s come at a cost to their signature high press, which this year has fewer bodies forward (and one of those bodies might as well be a wax figure of Mitri). But they are still one of the league’s most effective teams at doing their defending in the opponent’s half.

Interestingly, there’s not much of a pattern to which parts of the field their opponents’ threatening pass chains travel through, which is a little surprising given how heavily left-sided NYCFC’s own possession game is. That points to maybe the biggest strength of Dome’s new style: NYCFC is getting caught in transition less often. They are committing fewer turnovers in their own half and those turnovers are leading to less danger. And attacking with speed rather than numbers is making them harder to counter against—only San Jose allowed fewer expected goals from fast breaks.

WHY NYCFC WON’T WIN THE MLS CUP

LAFC. Duh.

In all seriousness, there’s reason to be concerned that NYCFC isn’t comfortable controlling the game in the opponent’s half. Look at any great team’s touch map—City, Liverpool, LAFC, Barcelona, you know, the global elite—and you’ll see them playing soccer in the middle of the opponent’s half, not off to one side of their own. In an intense playoff game, the ability to recycle possession while pinning the opponent deeper can be the difference between NYCFC’s usual poise and their panic against Atlanta last October.

But in even more seriousness, LAFC.

WHY NYCFC WILL WIN THE MLS CUP

For starters, home advantage. Thanks to the new single-leg format, at least two of the three games NYCFC needs to win to hoist a trophy will be played at home (or a reasonable facsimile thereof). Given that the home team wins a knockout game about two-thirds of the time, that alone would make them favorites to earn a shot at the cup final.

The other big thing this team’s got going for it is flexibility. Will they play a 3-4-2-1, a 4-2-3-1, a 4-2-2-2, or cycle through all three in the same half? NYCFC is effective in a dizzying array of shapes, which makes them practically impossible to gameplan against. They may be the top seed, but they are also the wild card.

Slow, then fast: that’s how Dome turned NYCFC into a serious MLS Cup contender. Maybe this nerdy website’s worth reading after all.

Thanks to Eliot McKinley, Cheuk Hei Ho, and Jamon Moore for their cool vizzes.