The case for pulling the goalie in soccer and the math behind Ben Olsen's madness

/By Jared Young (@jaredeoung)

The game is ice hockey. One team is behind a goal as the seconds wind down. Conventional thinking for the head coach of the losing team is to direct the goalie off the ice while a substitute enters the game. This gives the team a six to five player advantage at one end of the ice, but gives the leading team a much higher chance of adding to their lead. Starting in 2013 NHL teams became more aggressive with this strategy, and a paper released earlier this year proposed that teams should get at least three times as aggressive as they are. The math clearly lines up with the strategy.

Why is the game not soccer? In the world of soccer pulling the goalie is a rare occurrence. Sightings are limited to the heart throbbing final seconds when the tall brightly colored goalie runs into the box to add a body for a corner kick, and then sprints back as soon as the kick result is decided. Then there was the noteworthy call by Ben Olsen of D.C. United to pull his goalie near then end of a TIED game against Orlando, just before the famous Wayne Rooney play that saw them win the game. That specific decision will be dissected toward the end of the analysis, after groundwork for that risk is laid out. But what’s so different about soccer that goalies don’t leave the net more often, as they do in hockey?

There are a handful of anecdotal reasons the end of a soccer game is different than a hockey game. The first is that adding effectively a 12th player to the offensive end (pretend the goalie is counted twice for a moment) versus the other team’s 11 (9% more) doesn’t gain as much of an advantage as does a hockey team that gains an advantage of six versus five (20% more). Further, in hockey the goalie is replaced by a more skilled player in terms of goal scoring. In the case of soccer the coach has likely already used all of the substitutes, and goalies are not adept at possession or goal scoring, and therefore wouldn’t be able to add as much value going forward.

Lastly, the move that almost all soccer coaches make is to send forward one of the three or four defenders, a more conservative way to increase the numbers in the offensive end. That in theory would also tilt the chance of scoring in favor of the trailing team, without taking the risk of abandoning the goal, and perhaps why the goalie is kept in place.

These reasons might be enough to convince some that pulling the goalie is a bad idea in soccer, but they’d be wrong. The reason pulling the goalie in hockey works is not because of player ratios, defender options or goalie scoring skills, but because of the risk reward dynamics inherent in the game, and those are no different in soccer.

The reward in hockey and soccer are points, earned by winning or drawing an opponent. The loser of the game gets zero points. As the clock winds down, if a team is faced with earning zero points there is a point as which there is no downside risk, while there is a small chance of a reward. Having a potential reward for no risk becomes a compelling proposition, regardless of the specific dynamics of the sport.

It’s reasonable to assume that only one goal can be scored across 30 seconds in a soccer match. Between the celebrations and moving the ball back to the middle of the circle there are almost no goals scored that close together. Now assume the there are 30 seconds left in a game where a team is losing by a single goal. If the goalie were to run up and help, assume an absurd worst case scenario that the leading team will score 90% of the time. But let’s also assume that the extra body increases his team’s chance of scoring in those 30 seconds by an equally absurd 1%. Barely perceptible. Still, by bringing the goalie up the team’s chances of collecting a point have gone up while the cost of conceding a goal 90% of the time is still zero. The risk (zero) is the worth the reward (something).

Clearly a soccer goalie should, at the very least, abandon their goal during the last 30 seconds of a match in which the team is down a goal. Yet in all of the soccer matches all around the world, this action almost never takes place.

Time to put some real data to this problem and determine just how early a goalie should be pulled in a soccer game. While soccer does not have data on the impact of goalies leaving their net, the sport does have ample data on the value of one team having more players than another. Looking back through all of the MLS seasons since 2015 I calculated the rate at which home and away teams score during different situations of uneven strength.

At even strength home teams score goals at a rate of 0.009 every 30 seconds while away teams score at a rate of 0.0057 per 30 seconds. When one team has an advantage those numbers jump 58% higher. That rate is almost identical for home or away teams. When a home team has an 11 versus 10 player advantage they score .0142 goals every 30 seconds and away teams with the same advantage score 0.009. This lift is a good deal less than the advantage cited in hockey. The 2018 paper referred to earlier said that teams increase their rate of goal scoring by nearly 100% when pulling their goalie. The difference can be reasonably attributed to the fact that in hockey a 6th player against five is a bigger advantage than a “12th” player versus 11.

Soccer data generally does not note the moments when a goalie leaves the net, but we can start with the data from the hockey analysis and run sensitivities to get a sense of what soccer teams should do. Hockey teams when facing an opposing empty net increase their rate of scoring by four times. How that rate compares to what soccer teams would do is hard to gauge. On the one hand, the increase in players would work against defending teams because there are more players to cover gaps that emerge. The soccer pitch however is significantly larger, as is the goal, creating more space for the opponent to operate within. Your guess is as good as mine.

For reasons made earlier adjustments should be made to the rates at which goals are scored. The 58% increase in goal scoring rate should be reduced for two reasons. First the fact that the leading team is playing with a full 11 players, whereas the data is based on a team having only 10. The next adjustment is for the fact that a soccer goalie is not the same value as a field player when added to the squad. The 11 vs 10 impact should be roughly 10% and the field player impact will be 20%. The lift in goal scoring rate is now 42% to account for those factors. A more than four to one goal scoring rate disadvantage for pulling the goalie in hockey is increased to an eight to one disadvantage in soccer.

With these assumptions a model can be built. Pretend an away team is down a goal at whatever point in the game. What is the expected points a team has if they choose to pull their goalie?

Going back to the 30 second scenario earlier the away team has an expected points total of .0057, but by pulling the goalie they increase that rate to .0084 and gained .0027 points. The model now works backwards and assumes that if an even state is reached that the goalie goes back between the pipes. Here is a chart of the expected points scored by a home team in a normal situation versus a situation where the goalie joins the attack.

The middle line of the chart shows the home team can gain a maximum of about .02 points by pulling the goalie roughly 4.5 minutes before the end of the game. This would normally be right about the 90th minute. Home teams tie the game from that point nearly 13% of the time, so the benefit here is increased by roughly 16%. If you think that an opponent is less likely to score than in hockey that increase could be 50% higher.

Here are the slightly worse odds for the away team.

The advantage of pulling the goalie isn’t nearly as much as it is in hockey, which reported 1.5 points per season if the goalie is pulled at an optimal time. Given the reduced frequency of goal scoring the advantage is reduced to something in the quarter of a point range, but perhaps there are ways this can be optimized. After all, why do coaches really only pull the goalie on corner kicks, much like Olsen did in that famous game against Orlando City SC?

Counter attack goals from a corner kick are fairly rare. American Soccer Analysis compatriot Eliot McKinley (@etmckinley) examined shots attempted by the opponent 30 seconds after a corner kick. Opponents score just 0.24% of the time directly following an opponent’s corner kick since 2015, which is roughly one fifth as often as a team typically scores on any possession. Coaches must feel confident that a counter attack could reasonably be snuffed out, and the data would back that up.

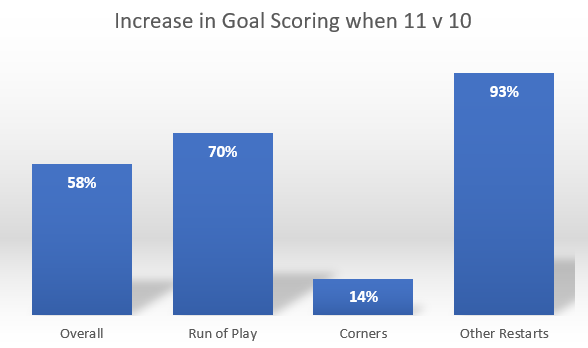

The problem with bringing the goalie up on corner kicks is that there isn’t that much of an advantage. Here are the advantages gained when up a player by situation.

The advantage gained from having an extra player is mostly from the run of play and other restarts, like final third free kicks. Corner kicks don’t reveal much of an advantage probably because of the density of the players around the goal. Coaches should actually be bringing up goalies more often and under different situations, especial free kicks where the benefit is greater and the potential to stop a counter attack is probably still very good.

Which brings us to Ben Olsen. He brought up a goalie in a 2-2 tie on a corner with about a minute left. In so doing he increased his team’s chance of scoring by something slightly north of 10% (discounting the 14% gain observed in 11v10 situations), which was worth roughly .0056 points (probability of scoring on a corner of .028 since 2015 * 10% * 2 points gained). But in this case he put a point at risk. Given corner kicks don’t give up many counter attack goals let’s assume that Olsen only doubled Orlando’s chance of scoring in the next 30 seconds. He sacrificed a mere .0024 points to gain that advantage, definitely worth the risk. If he had quadrupled Orlando’s chance of a counter then it would not have been a good bet. But given D.C. United is desperate for points down the stretch to make the playoffs, there was little to lose.

So why don’t more soccer coaches pull the goalie like Olsen, especially in games where points matter and the amount of points needed to achieve a goal becomes clearer and clearer? When a team is behind there is incentive to increase the level of risk taken. Pushing up defenders is certainly one move, but why not take the ultimate risk and send the goalie?

From a psychological point of view, the fans will certainly get behind the risk taking, just like they do in hockey, and the players should be mature enough to handle a potentially wider loss. To better understand the impact and begin optimizing end of game decisions, coaches need to take this risk so that more data will be available to understand just how good or bad a decision it can be.