Pass Chain Analysis: Should Teams Build From The Back?

/By Jamon Moore (@jmoorequakes)

Introduction

As I do on most Saturdays and the occasional Sunday, I was sitting at a youth soccer game last fall. My son - now playing 11v11 - had switched clubs over the summer, and I had heard how the new coach (who is also the club’s Director of Coaching and spent a few years in MLS in the late ‘90s) had a very particular playing style.

In our first difficult match of the season, we were down 0-2 early. At least one of our centerbacks seemed overmatched, putting pressure on the goalkeeper -- my son, who had been converted from midfield two years back.

“We always play out of the back, regardless of the score,” said a parent. “The coach says it’s important for player development.”

As a mostly-lapsed coach, I’ve read a significant amount of US Soccer literature. And hey, I like to think the keeper was good with the ball at his feet. So I “get it” – and, for the most part, I was happy to hear it (and happier to later discover we don’t play out of the back on ill-kept grass fields).

The parent went on, “We’re down today because we’re playing too slowly. We need to pick up the pace; we’re getting closed quickly and not handling the pressure.”

This isn’t a knock on the quality of play in MLS, but a lot of our favorite teams face the same issues as my son’s. Pressure means that balls are lost in an instant in poor positions, leading to quick counters by the opposition. Teams adjust by hitting the ball long over the pressure, and fans lament that “we’re not capable of playing out of the back” or that “we play too slowly.”

This made me wonder: what’s so great about playing out of the back anyway? I have heard coaches give the standard answers, and I get the advantages of the times you do successfully “get out,” but how well does this work in MLS where the current narrative is the attacking is better than the defending? When players several years older than my son can hit a ball 70 yards and change the point of attack in an instant, why would teams make several passes forward, backward, and sideways to cover the same ground? These are philosophical questions that different coaches and their teams answer each game with their choices and execution.

Back to Where the Ball Was Won

In my last ASA article, I discussed how passing data could be used to understand where teams were winning balls as an indicator of where they were drawing their lines of pressure. We found that teams which won the ball higher up the pitch generally accumulated more points this season in MLS. I also noted that it didn’t so much matter where teams made their attempts to win the ball, so long as they had an effective strategy in doing so.

The key for this is transition. If a team can quickly decipher the best path to get to the goal with the highest quality shot, they will be more successful. Presumably the higher up the pitch the ball is won, the shorter the path to the goal and the more success a team will have in getting that shot of highest quality. If only there weren’t opposing players between the ball and the goal…

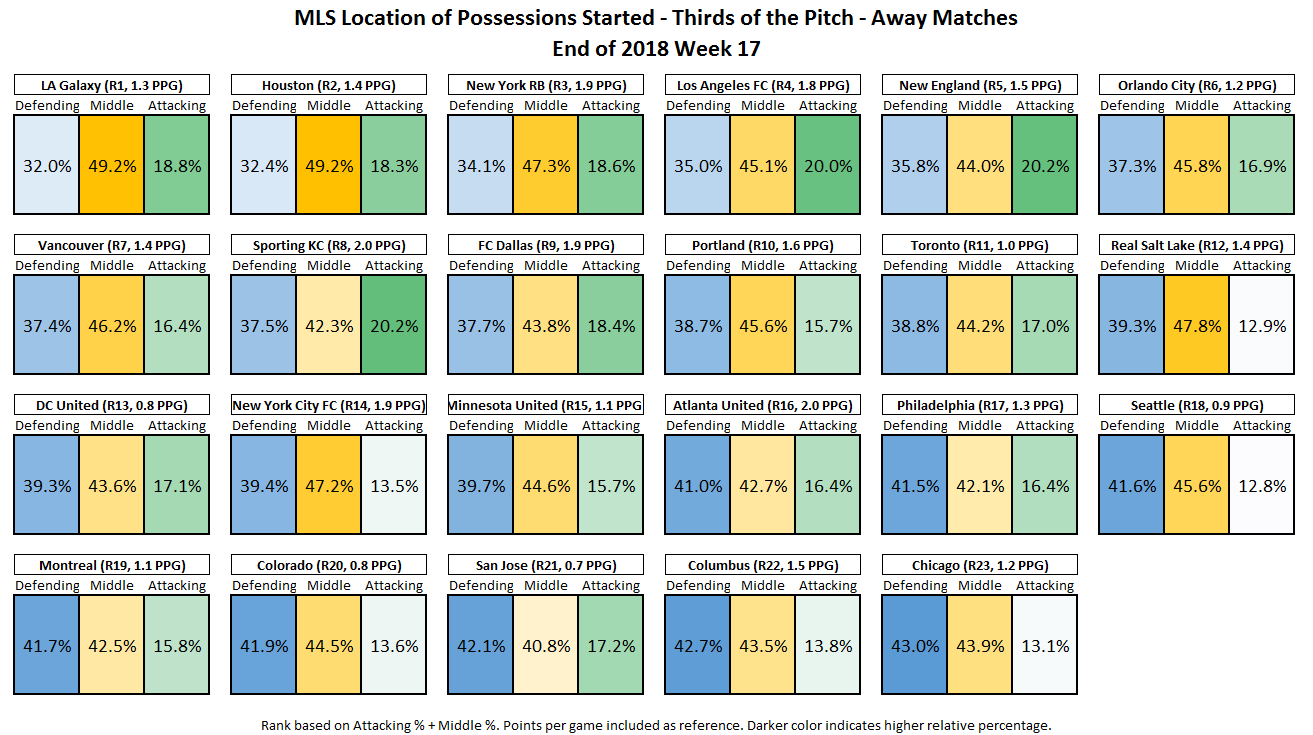

Here is updated data through Week 17 for a key visualization from the previous article. This visualization shows teams ranked by their combined winning percentage in the attacking and middle thirds.

And, by popular request, here are home and away slices of this same data, not provided in the previous article:

In these home and away breakouts we see some very interesting differences for teams such as Portland and Seattle who clearly play much more aggressively at home.

Passing Chains: Linking Where Possession Starts and Ends

Atlanta ran an actual three-man weave on a corner kick play and it was glorious. pic.twitter.com/ZVMOi9JGsk

— Bobby Warshaw (@bwarshaw14) June 24, 2018

Since my last article was published, Cheuk Hei Ho has published two incredible articles here on ASA which also discuss concepts of defensive pressure and how just a few additional possessions a game can have a major impact on the match outcome. If you haven’t read them, please go read them right now. Chuek Hei and I may not be able to execute a 3-man weave with just the two of us, but these articles are going to cross over with each other a bit.

However, my use of passing chains will differ slightly from Cheuk Hei’s definition of possession. He allows for quick recoveries within two seconds to maintain possession. Any incomplete pass will break my passing chains.

As passing data is being used to see where possession is starting, the logical extension is to see where possession is ending. Along with that, we can check how long possession lasts, how many passes are being made and much more.

First we order passing data within a match by time elapsed. So long as the same team is making the pass, we can assume that the possession has continued, and we increase the passing chain by increments of one. If the pass is not coming from a corner kick or free kick, then we can record the amount of seconds between passes. By checking coordinate data, we can see if the next pass is happening immediately from the same location or if the player with the ball has changed their position -- presumably with a dribble. The table below is sorted alphabetically by team.

| Full Name | Games | Total Passing Chains | Passing Chains per Game | Average Passing Chain Length | Move After Pass % | Average Time Between Passes (seconds) | Average Passing Chain Duration (seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta United | 17 | 2030 | 119.4 | 3.46 | 53.10% | 3.008 | 12.09 |

| Chicago | 17 | 2053 | 120.8 | 3.18 | 46.20% | 3.069 | 11.05 |

| Columbus | 18 | 2313 | 128.5 | 3.42 | 48.90% | 2.888 | 11.22 |

| Colorado | 15 | 1706 | 113.7 | 2.58 | 41.10% | 2.908 | 8.48 |

| DC United | 12 | 1426 | 118.8 | 2.81 | 44.20% | 2.842 | 9.56 |

| FC Dallas | 15 | 1789 | 119.3 | 3.11 | 48.50% | 3.008 | 10.86 |

| Houston | 15 | 1828 | 121.9 | 3.03 | 45.00% | 3.002 | 10.5 |

| Los Angeles FC | 15 | 1905 | 127 | 3.3 | 55.80% | 2.903 | 11 |

| L.A. Galaxy | 15 | 1850 | 123.3 | 3 | 46.70% | 2.845 | 9.83 |

| Minnesota United | 15 | 1847 | 123.1 | 2.97 | 49.50% | 2.671 | 8.99 |

| Montreal | 17 | 2090 | 122.9 | 2.95 | 49.90% | 2.913 | 10.04 |

| New England | 16 | 2096 | 131 | 2.4 | 39.80% | 2.908 | 7.93 |

| New York City FC | 16 | 2328 | 145.5 | 3.31 | 41.70% | 2.645 | 10.31 |

| New York | 15 | 2035 | 135.7 | 2.38 | 38.50% | 2.654 | 7.08 |

| Orlando City | 16 | 2127 | 132.9 | 3 | 50.00% | 2.866 | 9.47 |

| Philadelphia | 16 | 2116 | 132.3 | 3.18 | 51.30% | 2.976 | 10.97 |

| Portland | 14 | 1610 | 115 | 2.88 | 48.10% | 2.906 | 9.71 |

| Salt Lake | 16 | 2090 | 130.6 | 3.11 | 50.00% | 2.955 | 10.78 |

| Seattle | 14 | 1809 | 129.2 | 3.09 | 45.70% | 2.887 | 10.19 |

| San Jose | 16 | 1970 | 123.1 | 2.78 | 40.00% | 2.913 | 9.22 |

| Kansas City | 16 | 2253 | 140.8 | 3.45 | 50.00% | 3.039 | 12.21 |

| Toronto | 15 | 2095 | 139.7 | 3.42 | 56.10% | 2.873 | 10.96 |

| Vancouver | 17 | 1865 | 109.7 | 2.8 | 41.10% | 2.934 | 9.61 |

| Average | 15.6 | 1966.6 | 126.3 | 3.04 | 47.00% | 2.9 | 10.15 |

New York City FC has the most passing chains per game with 145.5 and is in the top third in passing chain length (3.31). They don’t move much with the ball between passes (41.7%). This allows them to have the shortest time between passes in the league (2.645 seconds). They pass more and dribble less. In other words, NYCFC play quicker than everyone else. Unsurprisingly, the New York Red Bulls have the shortest passing chain in the league with 2.38 and the shortest chain duration average with 7.08 seconds. They actually dribble the least between passes (38.5%), while falling just short of their cross-city rival in time between passes at 2.654 seconds. The significant difference in playing styles between the New York teams leads to a similar result in this case.

If Sporting KC fans have said, “we play the slowest in the league”, they were right. But their league-longest passing chains are part of their master plan. Sporting KC had the longest passing chain of the season back on May 10 at Atlanta United, a 39-pass chain with two (backward) long balls and ending with an unsuccessful cross.

The previous table also shows that Toronto likes to dribble with the ball a lot (at 56.1% of the time) between passes, and LAFC sure seems jealous about it (55.8%).

This visualization shows where passing chains end for each team:

The results here don’t give us much of anything. Just like we saw Columbus was among the top teams at winning the ball in their defensive third, they also lose the ball the most in the defensive third. This could be just due to volume -- there doesn’t seem to be much correlation here to team performance.

As much as I want to get into the “how” of teams losing the ball, I am most interested in learning if MLS teams play better out of the back or through long balls. First let’s look into which teams are effective at moving the ball from the defensive zone to the middle and attacking zones. This visualization is sorted by the percentage of balls won in the middle third which are moved to the attacking third:

This is a bit more like it, but the percentages may still be a little misleading. NYCFC is ranked 21st, and is actually the most backward team, losing the ball in the defending third after winning it in the middle third 13.7% of the time. However, what really matters is how many times they move the ball from the middle third to the attacking third and in that metric, NYCFC is actually 6th overall.

In the visualization above, you can look at the “Tot R” value in each team’s header for their ranking based on volume. So while FC Dallas is ranked 4th in efficiency (by percentage), they are 15th in volume. Portland has a similar problem – 6th in efficiency, but 20th in volume.

MLS Passing Chains and Times - Middle Third to Attacking Third

| Team | Name | Avg Chain | Avg Chain Time | Avg Pass Time | End in Key Pass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATL | Atlanta United | 4.83 | 13.65 | 2.83 | 16.60% |

| CHI | Chicago | 4.34 | 12.39 | 2.85 | 12.70% |

| CLB | Columbus | 4.43 | 13.25 | 2.99 | 14.10% |

| COL | Colorado | 3.18 | 9.14 | 2.87 | 15.30% |

| DCU | DC United | 3.7 | 11.09 | 3 | 13.20% |

| FCD | FC Dallas | 3.98 | 12.59 | 3.16 | 17.00% |

| HOU | Houston | 3.82 | 10.94 | 2.87 | 18.40% |

| LAFC | Los Angeles FC | 4.58 | 13.42 | 2.93 | 18.30% |

| LAG | LA Galaxy | 3.74 | 10.4 | 2.78 | 14.00% |

| MIN | Minnesota United | 4.08 | 9.95 | 2.44 | 10.10% |

| MTL | Montreal | 4.08 | 11.56 | 2.83 | 14.90% |

| NER | New England | 3.06 | 10.19 | 3.33 | 10.90% |

| NYC | New York City FC | 4.54 | 11.51 | 2.53 | 11.60% |

| NYRB | New York RB | 3.03 | 7.56 | 2.5 | 13.00% |

| ORL | Orlando City | 3.88 | 11.54 | 2.98 | 10.40% |

| PHI | Philadelphia | 4.67 | 14.45 | 3.09 | 13.60% |

| POR | Portland | 3.98 | 10.46 | 2.63 | 14.70% |

| RSL | Real Salt Lake | 4.13 | 10.59 | 2.56 | 17.40% |

| SEA | Seattle | 4.2 | 10.75 | 2.56 | 14.20% |

| SJE | San Jose | 3.71 | 9.1 | 2.45 | 15.40% |

| SKC | Sporting KC | 4.44 | 14.06 | 3.16 | 16.60% |

| TOR | Toronto | 4.64 | 13.89 | 2.99 | 14.20% |

| VAN | Vancouver | 3.42 | 10.25 | 3 | 17.20% |

Houston and LAFC are the most efficient at generating a shot by winning the ball in the middle third and then advancing the ball to the attacking third. In looking at chain length and time for these situations we can see the Red Bulls are still the Red Bulls with the shortest passing chains, while Atlanta United have the longest. These teams also have the shortest and longest average passing chain times. New England is the slowest to transition from the middle third to the attacking third on a per-pass basis, while Minnesota United are the quickest -- with San Jose a surprising hundredth of a second behind them.

Now we get to the big question – which teams are most efficient playing out of the back? That is, who moves the ball from the defending zone to the attacking zone with the highest efficiency and volume? The following table is sorted by the percentage of times a team is successful in moving the ball from the defending third to the attacking third:

MLS Passing Chains - Defensive Third to Attacking Third

End of 2018 - Week 17

| Team | Full Name | PPG | Chains Starting in Def Third/game | Def 3rd to Atk 3rd Chains/game | % Success Def to Atk 3rd | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKC | Sporting KC | 2 | 46.6 | 10.4 | 22.30% | 1 |

| CLB | Columbus | 1.5 | 52.3 | 9.4 | 18.10% | 2 |

| ORL | Orlando City | 1.2 | 48.2 | 9.1 | 18.80% | 3 |

| TOR | Toronto | 1 | 51.2 | 8.7 | 16.90% | 4 |

| LAFC | Los Angeles FC | 1.8 | 44.1 | 7.9 | 18.00% | 5 |

| RSL | Real Salt Lake | 1.4 | 49.6 | 7.8 | 15.80% | 6 |

| ATL | Atlanta United | 2 | 44.2 | 7.6 | 17.20% | 7 |

| MTL | Montreal | 1.1 | 49.4 | 7.5 | 15.10% | 8 |

| FCD | FC Dallas | 1.9 | 43.6 | 7.2 | 16.50% | 9 |

| POR | Portland | 1.6 | 44.3 | 7.1 | 16.00% | 10 |

| SJE | San Jose | 0.7 | 49 | 6.9 | 14.00% | 11 |

| LAG | LA Galaxy | 1.3 | 40.3 | 6.9 | 17.10% | 12 |

| HOU | Houston | 1.4 | 37.7 | 6.7 | 17.90% | 13 |

| NYC | New York City FC | 1.9 | 50.8 | 6.6 | 12.90% | 14 |

| SEA | Seattle | 0.9 | 48.4 | 6.4 | 13.30% | 15 |

| NER | New England | 1.5 | 41.4 | 6.2 | 15.00% | 16 |

| PHI | Philadelphia | 1.3 | 44.2 | 6.1 | 13.70% | 17 |

| MIN | Minnesota United | 1.1 | 45.9 | 6 | 13.10% | 18 |

| CHI | Chicago | 1.2 | 47.1 | 5.9 | 12.60% | 19 |

| COL | Colorado | 0.8 | 44.3 | 5.9 | 13.40% | 20 |

| NYRB | New York RB | 1.9 | 46.1 | 5.9 | 12.70% | 21 |

| DCU | DC United | 0.8 | 46 | 5.7 | 12.30% | 22 |

| VAN | Vancouver | 1.4 | 38.7 | 5.1 | 13.20% | 23 |

Finally we may have the answer to what Columbus, who has been at or near the end of every visualization until the last two, is doing: they are getting the most possessions (52.3) from the defensive third to the attacking third. The Crew have 200 more passing chains which start in the defensive third, and at the 3rd highest efficiency they get more through the opposing midfield than others.

Sporting KC tops the efficiency list, which is no surprise. Their margin of almost 4% is significant; it is a strong indicator that Sporting KC is the best team in MLS at playing out of the back. It may be surprising to people to see NYCFC and the Red Bulls so low here, but their high possession and very direct styles work well coming out of the middle third and tend to fail when they need to come all the way from the back.

But while Columbus and Sporting KC do well in moving the ball from the back to front, does this result in shots? And do teams play with a higher tempo when playing out of the back?

| Team | Name | Avg Chain | Avg Chain Time | Avg Pass Time - Attacking Third | Avg Pass Time - Middle Third | Pass Time Difference | End in Key Pass | Resulting Key Passes per Game |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATL | Atlanta United | 7.33 | 21.05 | 2.87 | 2.83 | 0.04 | 22.50% | 1.81 |

| CHI | Chicago | 5.96 | 15.06 | 2.53 | 2.85 | -0.33 | 14.90% | 0.83 |

| CLB | Columbus | 5.89 | 15.71 | 2.67 | 2.99 | -0.33 | 11.80% | 1.25 |

| COL | Colorado | 5.11 | 13.63 | 2.67 | 2.87 | -0.2 | 13.50% | 0.8 |

| DCU | DC United | 5.94 | 14.55 | 2.45 | 3 | -0.55 | 8.80% | 0.4 |

| FCD | FC Dallas | 6.1 | 17.22 | 2.82 | 3.16 | -0.34 | 21.30% | 1.44 |

| HOU | Houston | 5.51 | 16.13 | 2.92 | 2.87 | 0.06 | 21.80% | 1.29 |

| LAFC | Los Angeles FC | 6.66 | 18.39 | 2.76 | 2.93 | -0.17 | 16.00% | 1.12 |

| LAG | LA Galaxy | 5.5 | 18.02 | 3.28 | 2.78 | 0.5 | 15.50% | 1.07 |

| MIN | Minnesota United | 6.42 | 14.95 | 2.33 | 2.44 | -0.11 | 16.70% | 1.07 |

| MTL | Montreal | 5.2 | 14.64 | 2.82 | 2.83 | -0.01 | 15.70% | 1.25 |

| NER | New England | 4.83 | 13.25 | 2.74 | 3.33 | -0.58 | 17.20% | 1.13 |

| NYC | New York City FC | 6.1 | 16.13 | 2.64 | 2.53 | 0.11 | 19.00% | 1.33 |

| NYRB | New York RB | 4.34 | 9.81 | 2.26 | 2.5 | -0.24 | 15.90% | 0.88 |

| ORL | Orlando City | 5.61 | 15.41 | 2.74 | 2.98 | -0.23 | 14.50% | 1.5 |

| PHI | Philadelphia | 6.23 | 16.78 | 2.69 | 3.09 | -0.4 | 15.50% | 0.94 |

| POR | Portland | 5.82 | 15.64 | 2.69 | 2.63 | 0.06 | 21.20% | 1.31 |

| RSL | Real Salt Lake | 6.37 | 18.81 | 2.95 | 2.56 | 0.39 | 25.60% | 2.13 |

| SEA | Seattle | 6.23 | 18.84 | 3.02 | 2.56 | 0.46 | 17.80% | 0.94 |

| SJE | San Jose | 5.25 | 16.23 | 3.09 | 2.45 | 0.64 | 19.10% | 1.4 |

| SKC | Sporting KC | 6.34 | 18.41 | 2.91 | 3.16 | -0.26 | 12.70% | 1.4 |

| TOR | Toronto | 6.94 | 18.48 | 2.66 | 2.99 | -0.33 | 18.50% | 2 |

| VAN | Vancouver | 4.47 | 12.28 | 2.75 | 3 | -0.25 | 13.80% | 0.71 |

DC United, Philadelphia and New England play around a half-second faster when moving the ball to the attacking third from the defending third, than they did going from the middle third to the attacking third, while LA Galaxy, San Jose and Seattle are all around a half-second slower.

Did anyone have Real Salt Lake in their highest-key-passes-generated-from-playing-out-of-the-back pool? Me neither. Only Toronto is even close to RSL. So while Columbus and Sporting KC are the most efficient getting into the attacking third from the defensive third, they are about average in getting a resulting shot from their efforts according chains ending in a key pass. So perhaps the answers to the Crew can be found somewhere in this amazing chord diagram from Eliot McKinley.

This is a chord diagram of #CrewSC's passes this season. Not sure how useful it is beyond being pretty, but it does show the influence of outside backs in Berhalter's system. pic.twitter.com/0qWS1VXWhy

— Eliot McKinley (@etmckinley) July 2, 2018

Coming back to Sporting KC, they are simply different from everyone else. They play slower and still manage to be very successful playing out of the back, in contrast to the speed with which possession teams like NYCFC play and quite unlike how most youth players are being taught to play: quicker, if not necessarily smarter.

To get a deeper perspective on what makes Sporting KC different, I chatted with Daniel Sperry who is a managing editor for Last Word on Soccer and writes for mlssoccer.com about the team. Sperry explained that SKC and Peter Vermes play with what they call a “pressure relief” system which manages space and handles pressure:

“They never have two players in the same channel. (Ike) Opara and (Matt) Besler usually sit with quite a large space between them and Ilie sits centrally between them, but in between the midfield and forward lines. While the buildup can be ‘slow’ vertically, they’re usually looking to find/create the space to play people in between the lines and in behind. They work the ball quickly around, switch a ton, until they get a look that allows them to play ‘north-south’ into the danger zones.”

One of SKC’s not-so-secret strategies is to bring Graham Zusi central into the buildup to help them get out, “so they do manage pressure better, but they do it by ensuring they don’t turn the ball over within the middle third, and they’re patient to find the right time/place to break that ball into the middle third.” Sperry said that Zusi gives them flexibility: “he ventures much more centrally than every other fullback, which is something that helps a lot. (This) almost gives them a fourth CM option inside if the wingers are pressing high as well.”

But there is one more question left to be answered: is it generally more efficient to play the long ball or work your way up the pitch in MLS? To answer this, I checked how many 30+ yard vertical long balls (VLB) each team is playing per passing chain starting from the defensive third and ending in the attacking third. By “vertical long ball”, I mean if the pitch was a set of coordinates with a mark for each yard on a typical 115 yd x 80 yd size, and the pitch length was the x-axis, the ball moved at least 30 marks forward on the x-axis in a single pass. Fewer forward long balls on average would be an indicator of a team that builds more out of the back. 30 yards was selected as the minimum distance for measuring long ball verticality given the close equivalence to the OPTA 35-yard long ball definition when looking at actual pass length.

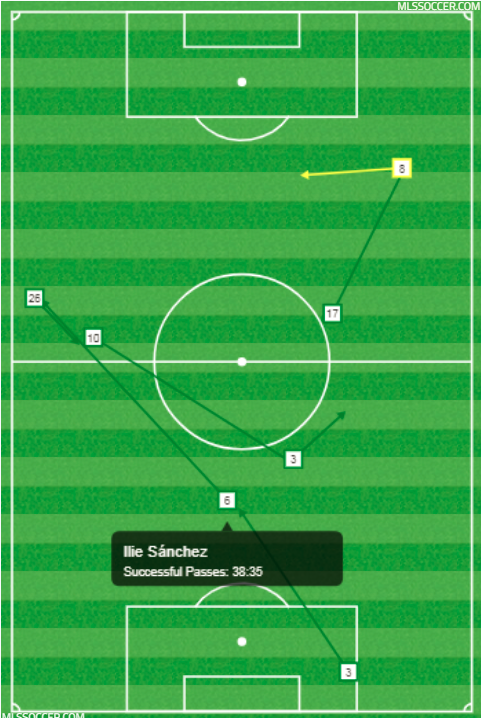

Here is a perfect example of a passing chain containing a vertical long ball and a key pass.

MLS Defensive Third to Attacking Third - Long Balls per Chain and Resulting Key Pass/Long Ball Correlation

| Team | Name | Chains from Def to Atk 3rd | Vertical Long Balls (VLB) per Chain | % VLB Accuracy | Chains Ending in KP with VLB | Chains Ending in Key Pass without VLB | % KP with VLB | % Def to Atk 3rd Passing Chains with KP and VLB | % Def to Atk 3rd Passing Chains with KP and no VLB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATL | Atlanta United | 166 | 0.6 | 29.60% | 9 | 20 | 31.00% | 28.10% | 20.60% |

| CHI | Chicago | 145 | 0.63 | 28.70% | 7 | 8 | 46.70% | 21.20% | 11.80% |

| CLB | Columbus | 170 | 0.31 | 46.80% | 14 | 6 | 70.00% | 33.30% | 4.70% |

| COL | Colorado | 119 | 1.03 | 21.10% | 5 | 7 | 41.70% | 18.50% | 11.30% |

| DCU | DC United | 101 | 0.71 | 37.70% | 1 | 5 | 16.70% | 3.70% | 12.20% |

| FCD | FC Dallas | 129 | 0.73 | 26.00% | 10 | 13 | 43.50% | 26.30% | 18.60% |

| HOU | Houston | 103 | 0.76 | 31.80% | 12 | 10 | 54.50% | 29.30% | 16.70% |

| LAFC | Los Angeles FC | 130 | 0.6 | 30.30% | 8 | 11 | 42.10% | 22.90% | 13.10% |

| LAG | LA Galaxy | 108 | 0.84 | 30.60% | 9 | 7 | 56.30% | 20.00% | 12.10% |

| MIN | Minnesota United | 99 | 0.67 | 24.30% | 5 | 10 | 33.30% | 29.40% | 13.70% |

| MTL | Montreal | 125 | 0.64 | 32.50% | 13 | 7 | 65.00% | 25.00% | 9.30% |

| NER | New England | 127 | 1.04 | 24.80% | 6 | 11 | 35.30% | 15.00% | 18.60% |

| NYC | New York City FC | 99 | 0.83 | 22.30% | 6 | 14 | 30.00% | 19.40% | 18.90% |

| NYRB | New York RB | 110 | 1.22 | 24.60% | 9 | 5 | 64.30% | 23.10% | 10.20% |

| ORL | Orlando City | 97 | 0.61 | 31.50% | 6 | 15 | 28.60% | 14.00% | 14.70% |

| PHI | Philadelphia | 89 | 0.71 | 31.30% | 8 | 7 | 53.30% | 24.20% | 10.90% |

| POR | Portland | 90 | 0.74 | 23.70% | 12 | 9 | 57.10% | 35.30% | 13.80% |

| RSL | Real Salt Lake | 87 | 0.52 | 30.00% | 16 | 16 | 50.00% | 39.00% | 19.00% |

| SEA | Seattle | 90 | 0.69 | 28.00% | 12 | 4 | 75.00% | 38.70% | 6.80% |

| SJE | San Jose | 105 | 0.95 | 27.70% | 10 | 11 | 47.60% | 23.80% | 16.20% |

| SKC | Sporting KC | 88 | 0.47 | 36.40% | 8 | 13 | 38.10% | 18.20% | 10.70% |

| TOR | Toronto | 101 | 0.49 | 27.30% | 10 | 14 | 41.70% | 28.60% | 14.70% |

| VAN | Vancouver | 68 | 1.26 | 26.50% | 6 | 6 | 50.00% | 13.60% | 14.00% |

| League | Averages | 110.7 | 0.74 | 29.10% | 8.78 | 9.96 | 46.90% | 23.90% | 13.50% |

Columbus is the most dedicated to avoiding the vertical long ball as only 31% of their passing chains have them. Deep passes are still a useful part of their arsenal: 70% of their passing chains between the defensive third and attacking third which have a key pass contain at least one vertical long ball, and they have the highest successful vertical long ball percentage (46.8%). They have the second largest difference between key passes generated from passing chains started in the defensive third when they use a long ball (33.3%) than when they don’t (4.7%). In other words, they are way more successful when they play the occasional long ball. Seattle has the largest difference with 38.7% with a long ball and only 6.8% without.

Vancouver, with only 68 successful penetrations from the attacking third to the defensive third, plays the most long balls in any direction per passing chain (1.26), but they only have a 26.5% success rate with VLBs. Given they have equal success, such as it is, with getting key passes without long balls, their reliance on long balls is clearly is just not working well for them. The Red Bulls have very similar issues, but they generate a lot more passing chains from the defensive third, so this problem is not as pronounced. DC United is tied with Vancouver for the fewest key passes from passing chains started in the defensive third.

League-wide, teams are 10% more successful generating shots from a pass when the passing chain includes at least one vertical long ball. And while there are many teams who benefit much more from using vertical long balls, on a shot generation basis per passing chain (last two columns in the above table), there really isn’t a team which clearly benefits from not playing long balls.

Conclusion

No single team in MLS clearly generates more shots when starting from the defensive third and using shorter passes. Given this, playing consistently out of the back with only short passes and horizontal long balls seems to be a much less effective strategy in the league in 2018, although an over-reliance on long balls could also have an adverse effect as seen with Vancouver. Long ball accuracy will have a big impact on the overall effectiveness of the strategy.

While not advocating teams stop passing their way of out of the back, there may be an over-emphasis on short passing and eschewing vertical long balls as the way to play. And after looking at this data, perhaps the thousands of hours the average USSDA MLS Academy (i.e., potential homegrown) player is practicing building out of the back isn’t all it’s cracked up to be and a more balanced approach should be implemented. More time could be spent on learning to hit accurate longer balls, and potentially more focus by coaches at both the youth and professional levels should be put on better space management rather than just playing quicker. Based on the data, it seems a team who can both hit the long ball accurately and manage space extremely well would be a major force to be reckoned with in this league – at least until the next seismic skill and tactical shift happens in MLS.