Postseason Preview: NYCFC

/Article by @thedummyrun

Domènec Torrent is a fraud.

Just four months ago, when he took over New York City Football Club midseason from Patrick Vieira, the Catalan coach was hailed as some kind of tactical savant, fresh off a decade seated at the right hand of Pep the Father Almighty and come down to MLS to save us all. He promised to preserve Vieira’s system, which after all was vaguely modeled on Manchester City’s, and to make only incremental adjustments. He promised to compete for trophies—if not this season, okay, maybe next year. He promised us the pinaple would be pretty.

The results have been anything but. Dome inherited an NYCFC side that sat a lofty third in the Eastern Conference on points per game and allowed them to slide all the way to, well, third in the Eastern Conference. Hmm okay bad example. But there has been genuine cause for alarm: Torrent’s points per game over his four months in charge have been a middling eleventh in the league, and from the start of September till last week only Orlando, Colorado, and San Jose were worse. Topping those three shouldn’t even qualify you for a participation trophy at your youth rec league’s season-ending pizza party.

Lately it’s been one big shame spiral in the Bronx. NYCFC lost at home to New England, as if Boston needed another sport to be happy about right now. They lost on the road to ten-man Minnesota (a team that is, to borrow Robert Frost’s description of Loons superfan Paul Bunyan, “a terrible possessor”). Six of NYCFC’s last ten games came against other Eastern Conference playoff teams, and until this week they’d gone winless in them. Fans were inconsolable. A #DomeOut hashtag started bubbling up on Twitter. The Extra Time Radio guys called NYCFC trash and bet a t-shirt on it. The club’s playoff hopes were widely written off.

But that, see—that was the fraudulent part.

The hideous lie that Dome has perpetrated on you, the pure-hearted men and women of the American soccer public, is to convince you that he’s made NYCFC worse. Oh sure, he’s had help from league shills pushing propaganda about how his team has “come unglued in terms of how and where they press, what they do when they win the ball back, and how to even build from the back.” They were in on the act. Dome knew you’d buy it because, come on, just look at his wins and losses. Look at the lack of goals. He must be a bad coach, right?

Dome trusted you wouldn’t notice that even as the goals dried up, underlying stats were on the upswing. Dropping much-needed points to an opponent NYCFC outpossessed by 38 percentage points and outshot 31 to 2 was the perfect way to distract you from the fact that the team had spent the last few months quietly amassing more expected goals and conceding less than over any comparable period in the club’s short history. (Hey man, it’s hard to do math when you’re sobbing into a chicken bucket.) When xG did come up, fans who’d loved the stat in the summer had lost faith in its predictive power by fall. And nobody wanted to hear that the team was passing more often, more effectively, and closer to the other team’s goal than before, while opponents were doing the opposite. If the wins weren’t there, what good were numbers? Basically the whole #DomeOut scam depended on nobody reading this nerdy website—which, you know, fair enough.

Dome is no stranger to this kind of statistical skullduggery. In their first season at Manchester City, Guardiola and his coaching staff stumbled to a disappointing third-place finish, with zero wins against the rest of the top four. (You may recall the words “bald fraud” being bandied about back then.) By year two, City was transformed into the most terrifying juggernaut the Premier League had ever seen, and Dome spent most of his screentime in the retrospective Amazon miniseries clinking celebratory glasses of Rioja. What had changed? Training and transfers helped, sure, but some of it was just bad luck running out. Even when they had finished 15 points behind Chelsea in 2016-17, Guardiola’s City was putting up elite advanced stats, blowing the competition out of the water on non-penalty expected goal differential and expected points. Given enough games, a team that good at creating and denying quality scoring chances was bound to rise to the top.

NYCFC doesn’t have enough games left this year to do justice to its xG glow up. At most it’s got six games of knockout soccer, a wildly unpredictable format in a sport where goals are both flukey and rare. And the second and third games could come against Atlanta United, the only team with a better expected goal differential in the Torrent era. So if the goal here is to get an idea of the team’s playoff prospects, it’s not enough to drop a link to ASA’s interactive tables. Let’s take a closer look at how exactly Dome’s boys do the soccer.

The Lineup

Thanks to a constant drip of injuries, international call-ups, and failed attempts at figuring out how to fit Jo Inge Berget into the lineup, Torrent has yet to start what I figure is his best eleven. That should change this week. With Yangel Herrera finally fit and Ismael Tajouri-Shradi getting over a niggling ankle injury, Wednesday night’s knockout round game against Philadelphia should see the team at full strength for the first time since May.

Already in Sunday’s preview match we saw how dramatically Herrera can change NYCFC’s look. Gone were Ebenezer Ofori’s timid tackles and Fort Knox-safe passes, along with Eloi Amagat’s plodding veteran presence, replaced by an energetic Venezuelan destroyer who’s still somehow—yes, I had to check—not old enough to lick up any celebratory champagne should this team turn things around in the playoffs. At the time Herrera went down for ankle surgery in May, he accounted for 18.8% of his team’s defensive actions, the second-highest rate in the league after Minnesota’s Rasmus Schuller. This comes at the cost of the occasional lost ball, as Herrera’s more active than he is accurate with his forward passes, but that’s a tradeoff New Yorkers will be glad to take.

Jesús Medina is working his way back into shape as well, and his smart movement and probing diagonals as an inverted right winger add another dimension to the team’s attack. The only other expected change is Rónald Matarrita ending his ongoing exile as an all-purpose utility player to return to his rightful spot as NYCFC’s best left back. I could be wrong about that one, but we won’t go into it here—talking about Ben Sweat on the internet can only lead to heartbreak.

If City Football Group has a foundational stylistic idea—what tactics writers call a “philosophy”—it is that if you pile enough cash on the field in crisply wrapped bundles the weight will tilt the playing surface so that the ball rolls downhill into the opposing goal. But CFG’s second, slightly subordinated idea is that possession-based soccer is both successful and attractive and all of its teams should aspire to it. That means building from the back.

What building from the back means in practical terms is harder to pin down, if only because the way you do it is heavily influenced by the way your opponent presses (unless you’ve got Kevin De Bruyne or Sergio Busquets, in which case you do pretty much whatever you want). When an opponent sends two wide forwards to close down the center backs, as the Union frequently did in Philadelphia in August, one of NYCFC’s defensive midfield pair will almost always be left free in the middle. If on the other hand the pressing team aims to break the link between the center backs with a lone striker, the way Jim Curtin used Cory Burke last weekend at Yankee Stadium, the doctrinal response is to form a makeshift back three and dribble into the wide spaces (we’ll see some of this in a second). Sometimes this means dropping Alex Ring centrally in the salida lavolpiana, but on Sunday it was Anton Tinnerholm who hung back and allowed the center backs to shift to the left, a move Manchester City has also favored lately.

It’s easy to wander off into the tactical weeds here, so maybe it’ll help to pick out a few principles that are more or less consistent features of NYCFC’s buildup:

The Play Style

Sean Johnson looks for his center backs. This is pretty much the defining feature of a team that builds from the back, but NYCFC is especially dogmatic about it. Of starting goalkeepers, only Tim Melia averages fewer vertical yards gained per pass. Johnson rarely trusts himself with short forward passes to a defensive midfielder, so if the center backs are marked they’ll often split wide toward the touchline to provide a safer outlet or create space over the top.

Watch Callens and Chanot split wide all the way to the touchline on this early backpass. That's pure Guardiola and a statement of intent to build through RBNY's press. Here the play comes off well, but it's a bet on NYCFC's skill and precision that ultimately didn't pay off. pic.twitter.com/PNNuW8l6aL

— Dummy Run (@thedummyrun) May 9, 2018

Alexander Callens drives the buildup. As NYCFC’s most technical defender, completing 4.7% more passes than ASA's expected passing model projects, Callens is charged with creative duties in the team’s own half. While Chanot prefers longballs or safe outlets to the fullback when he’s not feeding it to his partner, Callens is more likely to break lines by working the ball inside to a defensive midfielder. There’s a reason his 11.6% touch percentage is the highest on NYCFC’s back line and his 2097 passes were the third most of any defender in the league this season.

When Callens (orange) and Chanot (blue) play together, Callens drives the buildup. He's much more likely to work the ball inside to a defensive midfielder (o), while Chanot prefers outlets to the fullback (+). pic.twitter.com/060gTvZhxs

— Dummy Run (@thedummyrun) October 27, 2018

The attacking phase starts on the wing. Once NYCFC breaks the first line of pressure, the tendency is either to look long for a center forward over the top (which works approximately never) or else to kick it out to the wing and then move forward as a group into a sturdy attacking shape (which is an objectively better idea but also less exciting I guess). The wide angles and yellow tinge to Alexander Ring’s pass sonar in the lineup diagram speak to his taste for long diagonals, while Herrera’s shorter game is more likely to involve passing triangles with the left back. Herrera’s return to the starting lineup this week shifted 47% of the team’s play into the left third of the field, where he and Callens dominated NYCFC’s possession back in the spring. In short passing situations, it usually falls to the left back to relay a ball from Herrera up the sideline to reach the winger in the attacking half.

Got all that? Cool, let’s see it in action.

This play picks up just after an Anton Tinnerholm throw in back to Maxime Chanot, who resets to a standard buildup with the usual shovel pass over to Callens. Burke tries to lead Philadelphia’s press by splitting the center backs, but his help is delayed because Herrera drifts upfield to stagger the lines, pulling Dočkal away for a second. Callens’ backpass to Johnson buys him time to backpedal out wide away from pressure, and by the time the ball returns to him Burke has given up and Callens is free to lead the move into the attacking half, gobbling up free yardage till the fullback commits and Callens can send it up the wing. This, incidentally, was the exact moment that an irritated Curtin decided he was going to yank his striker at the half.

Jim Curtin's explanation for subbing Burke off at halftime should be framed and hung in Callens' locker. pic.twitter.com/d7ctyG6PF8

— Dummy Run (@thedummyrun) October 29, 2018

At the end of the play Ben Sweat is able to get to the touchline and pull it back for David Villa, which is exactly how NYCFC wants to finish its possessions. But it’s not always quite that easy. Another hallmark of the team’s style under Dome is its skill at moving the whole team to the opponent’s half in order to break down a bunkered defense. We call that the attacking set.

Attacking Set

Soccer teams use all kinds of formations in the middle of the field, but when one team achieves sustained possession in the attacking half, tactics tend to converge on some universal constants. Most defenses will shape themselves into two lines of four with a couple of free forwards, while aggressive offenses will look to spread the field with some variation on the 2-3-5 that was the game’s default shape back in simpler, probably way more fun times.

I made a simplified breakdown of the offensive transition because, honestly I don't know, I need a better hobby. pic.twitter.com/QB7gl7oh0t

— Dummy Run (@thedummyrun) August 5, 2018

Getting to an attacking set often requires a fair number of passes to work the offense into the right shape, so teams that excel at it are usually the ones comfortable with long buildups. Not many teams can hold a candle to NYCFC on that count.

Possession summary and outcome MLS 2018

— Cheuk Hei Ho (@Tacticsplatform) October 9, 2018

Every possession is binned by # of touches, with the total # of possession normalized to league average per bin and plot with average xG of each possession. Two visualizations@AnalysisEvolved @etmckinley @thedummyrun @JmooreQuakes pic.twitter.com/tRLaeJfxar

But patience in the attacking half wasn’t always this team’s forte. Despite putting up strong possession stats in the first half of the season, Vieira’s NYCFC actually generated an above average number of shots from a fast pattern of play, holding the ball deep and then bursting forward when it found a hole in the press. Torrent has changed that, shifting possession forward to seize control of the area at the top of the opposition box known somewhat ominously in American soccer circles as Zone 14.

Not only does NYCFC use the middle of the field more—which is easier to do now that Maxi Morález, the team’s most important player, operates as a free-floating number 10 instead of sharing shuttling duties in Vieira’s 4-3-3—it also uses it differently. While under the old system passes from the central zone tended to be aimed straight into the box with a predictably low success rate or else recycled backwards, NYCFC is now more comfortable maintaining possession there and swinging the ball from wing to wing.

Working the ball wide is important because that’s where the five-man front can find numerical advantages and break through the back line with over- or underlapping runs. While one of either the winger or fullback holds the ball on the touchline, the other shoots the channel between the opposing center back and fullback. At the same time Morález or Villa scoots over to offer a lateral option at the corner of the box. Defenses are left with the anxiety-inducing choice between chasing the runner or leaving one of NYCFC’s best attackers facing goal in a dangerous spot. Either way, the end result is often a through ball to the touchline followed by a cutback from alongside the six-yard box toward the penalty spot. It’s a routine combo the best attacks in Europe have perfected, and while NYCFC hasn’t exactly got it nailed down yet, the data shows they’re creating more shots from the right areas lately.

Torrent has changed the way NYCFC creates shots, relying less on shallow crosses and more on cutbacks from the dangerous zone beside the six yard box. Color denotes the distance of a key pass's endpoint from the center of goal. pic.twitter.com/jJ0EBh9PPj

— Dummy Run (@thedummyrun) October 27, 2018

Whew, that was a lot of charts. Let’s cut to some tape.

This entire minute-and-a-half passage is textbook NYCFC, from the Callens-driven buildup to the cutback that’s blocked at the end. Watch the combination play on the wing and the repeated attempts to get a runner in the channel to that favored key pass zone. Watch Ring get open at the top of the box as the defense is pulled deep and toward the occupied wing, opening space for a cross. Watch Chanot and Callens push up to the halfway line, where they can quickly recover lost balls in the counterpress and recycle play up the wing again. This particular sequence won’t show up on xG tables, but it’s exactly the kind of patterned play that has cemented NYCFC’s attack as one of the best in the league even during the goal drought.

Pressing

Besides bringing numbers forward to break down a defense, the advantage of the attacking set is that it helps to structure the offense to scoop up lost balls, the way Callens does in the clip above. Unlike the Red Bulls’ Kloppian counterpress, which swarms the ball with a heavy horizontal shift and keeps opponents on the back foot via lightning-fast offensive transitions directly at goal, NYCFC takes a more zonal approach, with one or two players closing down the ball while the next line spaces itself to close passing lanes. The results aren’t quite as spectacular as RBNY’s pressing numbers, but they’re pretty close.

NYCFC’s opponents’ possessions tend to be short—here the normalized histogram drops below the league average after six touches. That’s a very good thing, since opponent xG per possession climbs steeply on any chain longer than that. Like most possession-centric sides, this team is built to defend high, and they’re very good at it. By passes per defensive action (PPDA), a popular metric that divides an opponent’s passes in some designated zone—typically their own half—by the defenses’ tackles, interceptions, and blocks in that same sector, NYCFC boasts the best high press in the league.

PPDA is probably a little misleading, though, since your average MLS defender’s response to the running of the Bulls isn’t to wait around to get closed down but to squeeze his eyes shut, snatch at his rosary, and mail it long. That’s where ASA’s expected passing model can give us a helpful second opinion on defensive pressure. Although the model doesn’t measure defense directly, it estimates pass completion probabilities by location, direction, pass type, and situation, sort of like how the expected goal model projects conversion rates based on the circumstances leading to a shot. Since similar passes will differ not just by the quality of the passer but also by the amount of defensive pressure applied to the pass, looking at opposing pass scores across a diverse sample of opponents can help us to isolate the pressure part. This metric’s not perfect either—for one thing, it turns out to be really hard to guess the intended destination of incomplete passes, especially if they’re blocked or overhit (though longball indicators help). But the model’s suggestion that NYCFC under Torrent applies the second-most defensive pressure to passes in the opponent’s half (allowing 3.8% fewer completions than expected, less than RBNY’s 5.2% but well above New England’s third-place 2.4%) feels about right.

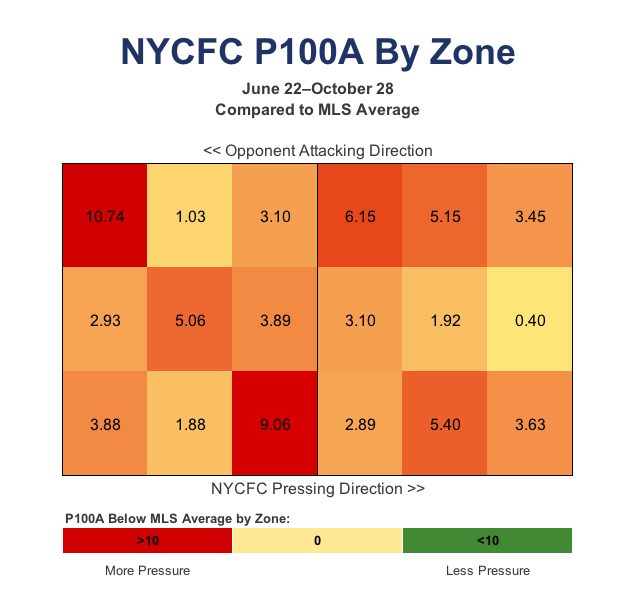

Expected passing scores per 100 passes against (“P100A” on the interactive tables) are probably also a more precise tool than PPDA for mapping effective pressure by zone, since defensive actions vary widely by defender style and tend to get pretty sparse in the attacking third, while xPass can give a decent account of passes anywhere on the field. Let’s see how NYCFC’s pressure under Torrent looks on a standard 18-zone (remember Zone 14?) pitch map.

It’s not all that surprising that NYCFC allows fewer completions than average everywhere on the map, nor that its pressure is strongest on the wings, where the press can trap opponents against the sideline. Some of the asymmetries may shake out differently now that Herrera’s hyperactive transition defense has returned to the left side of the field, but it’s a testament to Torrent and Ebenezer Ofori, who’s maybe a little more defensive than he gets credit for, that the team has maintained such a sturdy pressure map over the last few months.

Of course, not all high pressing is counterpressing, which is a term of art for pressure applied immediately after losing the ball. NYCFC brings an orderly high press against opponents that build from the back, too, starting with Villa between the center backs and wingers cutting off outlets to the fullbacks, but it’s not a situation that comes up much thanks to NYCFC’s league-leading possession and intense counterpressing. When opponents break through the counterpress, they rarely have time to reset before Torrent’s team borrows another page from the Guardiola playbook and burns a tactical foul to protect its high line. On a per-opponent-touch basis, NYCFC commits by far the most fouls in the league.

To bypass NYCFC’s high press and physical defensive transitions, opponents increasingly look to play long forward passes over the top, particularly up the right wing. You know why. Shhh.

Conclusion

There was supposed to be a whole ‘nother section here breaking down NYCFC’s defensive set, but I’m a humanitarian and you’ve suffered through enough of this already. Besides, opponents already know about NYCFC’s defensive weaknesses (hint: they’re on the side defended by Callens and, yes, Sweat).

It’s worth noting, though, that to the extent the team has suffered defensively lately (and they haven’t really—goals against have held steady around seventh in the league) it’s mostly a byproduct of goalkeeping. NYCFC’s expected goals against are third best in MLS since summer, but keeper save efficiency (a ratio of expected goals against in ASA’s goalkeeper model to goals allowed) has nosedived from a strong 109% under Vieira to 83% under Torrent. Some of that is Brad Stuver’s unfortunate two-game cameo, when he managed to allow 1.57 more goals than expected on just 9 shots. Some of it’s just Sean Johnson regressing to his typically average shotstopping numbers. Interestingly, opponent save efficiency has gone the exact opposite way over the same period, climbing from 85% to 104%. There’s not much reason to expect goalkeeping to stray from average on either side of the ball during the playoffs (unless they find themselves up against the white-hot Stefan Frei in an MLS Cup Final), so with any luck NYCFC should start scoring slightly more and conceding less than they have lately.

Which I guess brings us back where we started: stats and luck. Expected goals remain the best statistical predictor we have of a team’s future performance, and according to expected goals New York City Football Club has been a very good soccer team lately. Being very good at soccer is no guarantee you’ll get far in the topsy turvy world of the MLS playoffs, but it beats the alternative. Heading into the knockout round, ASA’s playoff prediction model gives NYCFC a 70% chance of advancing past Philadelphia and a 7.4% shot at lifting the MLS Cup. After all this team’s been through lately, that’d be a very pretty pineapple indeed.