Jurgen Klinsmann and the Guatemala Paradox

/The frustration with the state of the United States Men’s soccer team is at a new peak in the Jurgen Klinsmann era. After a disastrous second half of 2015 which saw them suffer historic losses to Jamaica and Panama in the Gold Cup followed by an extra time loss to rival Mexico, the Federation was hoping 2016 was a new beginning. But following another tragedy against Guatemala in World Cup qualifying on Friday, the U.S. has now failed to win its last four competitive matches where the talent gap was not obscene (apologies to St. Vincent and the Grenadines). The demons from last year are still lurking it appears. But to what can we attribute those demons?

Is it Klinsmann or the players?

What those demons are is the subject of much debate. Many claim that Klinsmann himself is the problem as questions surrounding his tactics, player selection and the positions he prefers for those players are appropriately criticized. After promises of progressing the U.S. style of play to compete with the more proactive national teams, Klinsmann has employed a more pragmatic reactive approach since before the World Cup. He likely regrets his promise as he’s since been unable to collect a midfield with enough talent to play a possession oriented style of soccer. When he trots Alejandro Bedoya and DeAndre Yedlin out to the wings, away from their preferred positions, in a World Cup qualifier he can't be expecting a cohesive midfield performance. Nor should the fans. But the team did waste too many balls in the final third attempting high risk passes. Do we blame the tactics, the players or both?

But it’s not all Klinsmann. The player pool and key injuries are also part of the problem. At forward there is the continually injured Jozy Altidore, an obviously less sharp Clint Dempsey, and Bobby Wood who is still finding his way. Aron Johannsson is out for an extended period as well, leaving questions marks about the future of the forward position. John Brooks and Matt Besler, perhaps the two best center backs, were both out of the game against Guatemala for various reasons. Bedoya was forced to the wing because Fabian Johnson was injured just days before the match. The United States has not been operating with their best team and the talent level of even their best team doesn’t instill much fear in opponents.

Whether its Klinsmann or the players who are responsible for this slide some statistics highlight how fine a line they both walk.

The Guatemala Paradox

Some might remember the 4-0 beat down that the United States gave Guatemala in a tune up before the Gold Cup last year. This result represented a peak period for Klinsmann. After a solid World Cup performance and friendly wins against Mexico, Netherlands and Germany, the United States was eyeing the Gold Cup and a return to the Confederations Cup. This 4-0 victory found the United States at the peak of their powers, stomping inferior CONCACAF opponents with ease.

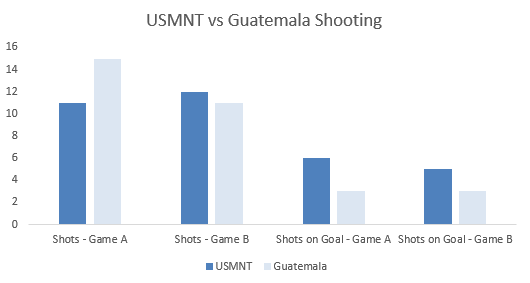

Here is a comparison of the shooting differential in both games against Guatemala

Which game was Game A and which one was Game B doesn’t really matter, because the shots were similar. But there was no chicanery intended in the chart. Game A was last July’s matchup. In Game B on Friday the U.S. actually increased their shots taken in the box from six to seven. Guatemala did as well. They increased their shots in the box from four to six. Overall the games were nearly identical from a shots point of view.

In terms of ball control the two games were also very much alike. The United States held 62.5% of possession in July according to mlssoccer.com and 62.8% of possession on Friday. Here’s how the passes were distributed.

The pass distribution was also very similar in both games. Last Friday the U.S. actually had more passes in the final third than in July, and they did less with those chances by completing just 62% of those passes, the same rate as Guatemala. The U.S. wasted those extra chances by launching long passes. Here are the passing charts of the U.S. in the two Guatemala games in roughly the final third of the pitch

images from mlssoccer.com

Notice the sea of long red lines in the lower right hand chart representing unsuccessful passing. The U.S. did find some success working the ball into the middle of the pitch whereas in July they either avoided that area or Guatemala’s defense was so compressed they forced them out wide. Notice in the red circles the difference in completed passes near the top of the box. It’s amazing the United States wasn’t able to take advantage of those advanced positions. In July the U.S. worked the ball out wide, especially to the left hand side, and found success with Graham Zusi and Gyasi Zardes. In the loss Bedoya (11 in the chalkboards above) struggled in the orange circles on the right, losing the ball more frequently than he advanced it.

But if you had to examine those charts without the labels and guess which one resulted in four goals and which one was a shutout you’d feel obligated to pull a coin from your pocket. The statistics leading up to the execution of the shots were nearly identical, but in the end highlight the USMNT’s paradox. The results could not be more contradictory, both in score line and in representing both the zenith and nadir of the Klinsmann regime.

The thin goal line

When the chances are the same what makes the difference between finishing the goal and not? On Friday night the U.S. had enough point blank chances but failed to convert. Both Bedoya and Dempsey put a pair of strikes on frame but right at the goalkeeper. Bedoya’s weak efforts were disappointing but not a surprise while Dempsey has done better with his in the past. The fifth shot on target, Altidore’s breakaway, was perhaps unlucky to catch the foot of Paulo Motta, who played a smart passionate game. Motta's well placed feet. A safe shot instead of one to a corner.

Back in July a penalty kick and an own goal helped the United States’ cause and a rare long blast from Timmy Chandler was the highlight the team lacked on Friday. An 86th minute break away from Zardes led to a tap in by Chris Wondowloski for the fourth and final goal.

So what made the difference in those moments? Was it the talent? Was it the players playing out of position? Was Guatemala's defensive pressure more intense so that it disrupted the shooters. Was it a failure of tactics that kept the players just out of sync? Were the players just not at their best? All else being equal, chances and all, what was the difference between four goals and none? Dare I ask was there any difference at all?

Klinsmann has at times played the master stroke, but he is also prone to decisions that fall very flat. Perhaps he lives too close to the edge, having faith in players where he should not, as he tries to push them where he wants them to go. Perhaps he knows they will fail him as often as they lift him. Perhaps that is giving him too much credit. But nine months after a run of victories over Mexico, Netherlands, Germany and a thumping of Guatemala, Klinsmann is facing his darkest hour as certain demons sit between that ball and the goal line. The United States will shortly take the pitch against Guatemala for a third time in nine months. Odds are they will hold more than 60% possession and create more shots on target. Will enough get through? Klinsmann's legacy may not get a bounce if they win, but if they don't you can be sure things will go absolutely dark.